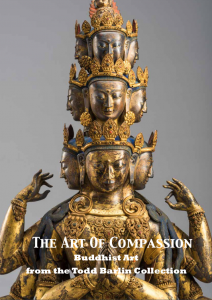

The Art of Compassion – Tibetan, Mongolian, and Burmese Buddhist Art. 慈悲的藝術 – 藏傳佛教藝術

| Collection No. | The Art of Compassion Catalogue |

|---|---|

| Size | N/A |

The Art of Compassion – Tibetan, Mongolian, and Burmese Buddhist Art

Catalogue available for $35 AUD Plus postage to your destination

Enquire Here

The great Buddhist exhibition The Art of Compassion is now showing at The Oceanic Arts Australia, Paddington, Sydney, Australia.

The exhibition contain Mongolian, Tibetan, Burmese Buddhist images and Figures.

With Essay by David Templeman

At the heart of all Buddhist art lies a sense of compassion. This compassion informs Buddha images as much as it does wrathful images who are merely another aspect of the more usually conceived gentle type of compassion. As any parent knows, true compassionate love for their child is not always a soft or comforting thing and to be effective needs to be tempered with its opposite. And so it is with the apparent contrast between the peaceful Buddhas and their wrathful forms – what we might regard as a separate ‘species’ of Buddhist art, that of wrath and violence, is in fact simply the same theme being looked at from a different side. This ‘Art of Compassion’ in fact reflects what we really are. Buddhism recognises that we are complex beings who are primarily united by a sense of love and compassion for our fellows despite any other differences which may exist to separate us. Buddhism teaches us that although there may appear to be many complex deities, it is at heart an atheistic system of practice in which the main goal is to regard the world and its inhabitants (including ourselves) with compassionate concern. This is in fact a sense of active stewardship in which we are all responsible for each other and live our lives with this as the main goal. Active compassion may adopt many forms and some of them may not be immediately recognizable as such. The above example of parental love is a case in point. The highest ideal of the Mahayana system of Buddhism found in China, Japan, Tibet and Mongolia is that of the Bodhisattva. This idealised person embodies compassion through their actions in the world. There is in them no sense of self, no sense of separateness from others and no sense of exclusivity. Their modes of action serve to inspire others to the same sense of a compassion which is deeply involved in the world as it is experienced. It is not a compassion ‘out there’ existing as a concept but rather it is something to be at the forefront of one’s mind at all times. It constantly asks a person difficult questions such as, ‘What can I do to help? What is the most skilful way to assist? Is this the most appropriate time to offer compassion? Am I exercising compassion for some selfish motive?’

As viewers of Buddhist art for the first time we may be struck from the start by the lack of light and shade on the painted surfaces noting that the subject is apparently uniformly lit with no attempt at chiaroscuro. This is because the Buddhist tradition of painting, even in ancient India, required no external light sources because, as Erberto LoBue notes, ‘…divine bodies do not receive light, they emanate it.’ (Lo Bue, E 2008, ‘Tibetan Aesthetics versus western Aesthetics in the Appreciation of Religious Art’, in Esposito, M (ed.) Images of Tibet in the 19th and 20th Centuries, Vol. 2, École Française d’Extrême-Orient, Paris). I would take LoBue’s observation a step further and suggest that rather than the deity radiating light exclusively it can also be claimed that the illumination of the focal deity is in fact as much due to the viewer bringing to the surface of the piece the illuminating light of their own insights, experiences and compassion. This gives the viewer an active role and a measure of involvement in viewing Buddhist art rather than relying on the image to ‘give’ something to them.

Karma and its Fruit

This idea of the viewer bringing their own light to the image makes complete sense in light of one of the three core beliefs in Buddhism – the law of Karma and its fruit, vipaka. Karma is simply the sum of the actions one performs in life and its fruit is the sum total of one’s good and bad deeds as well as one’s selfish and unselfish deeds. This ‘bank balance’ clearly shows the level of advancement or otherwise on the Buddhist path.

Impermanence and Unsatisfactoriness

Buddhist art is, at its most basic level, intended to bring about some personal reflection. It can be said to inspire faith in the sense of reminding the viewer that what is seen and experienced in life is only one dimension of what exists. Buddhism is said to be based upon a premise of the omnipresence of suffering. This is a bad translation of the word ‘dukha.’ A far better and more helpful one is its more exact meaning of ‘things as unsatisfactory.’ This translation reaches to the heart of Buddhist doctrine – that all things (including life, relationships, feelings) are unsatisfactory because at their heart they are not permanent and because as with most things, they bring with them a false sense of actually existing forever.

Buddhism says that accepting anything as if it were permanent is futile. So the question might be asked, ‘Are these Buddha forms also impermanent?’ and the response has to be a certain ‘Yes.’ This becomes clear when we look at the numerous images of Maitreya Buddha in the Exhibition. He is the Buddha of the next world-age and his name means, ‘Loving-Compassion’. To reinforce the core idea of the impermanence of all things further, there is no guarantee that even his teachings will be the same as those of the Buddha of our age, Shakyamuni Buddha.

Reconciling Opposites

In looking at the objects in this Exhibition, the viewer will be struck by the sheer simplicity of some pieces as well as the almost bewildering complexity of many others. Basically the collection may be seen as reflecting two halves of the enlightened human mind. The tranquil deities are as much a part of us as the wrathful, These complex figures have emerged from a Buddhist culture which has recognised quite readily that the human beings are composed of competing urges and that it is only in recognising them in all their bewildering variety and working with them that any progress on the path of becoming free from negativities and other hindrances may be achieved. The story of the 11-12th century poet- saint Milarepa who murdered in his youth reflects this overcoming of one’s past wicked deeds and there are several images of him to be seen in this Exhibition.